Researchers tracking the Atlantic Right whale have been somewhat concerned that the whales are not showing up in their usual summer feeding grounds in and around the northeastern US and eastern Canada.

They are now using sophisticated technology to try to find the whales in a project called WHaLE (Whales Habitat Listening Experiment).

Kimberley Davies (PhD) is a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Oceanography at Dalhousie University, Halifax, and co-manager of the Marine Environmental Observation Prediction and Response Network (MEOPAR) WHaLE project.

Listen

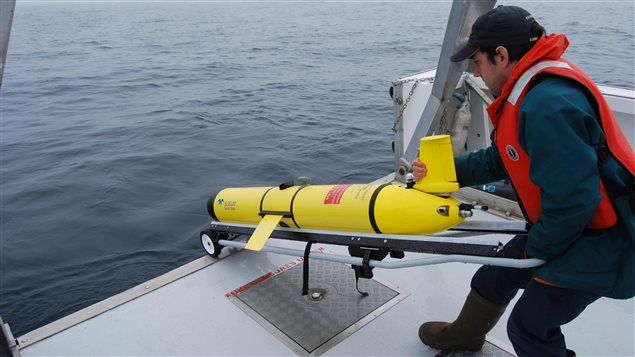

The technology the project uses is called a ‘glider’. It’s an autonomous vehicle that travels on a programmed path through the ocean picking up and identifying whale calls. The torpedo like devices can go to a depth of 200 metres, and detect whale calls up to 100 kilometres away.

It can differentiate the calls of various species, and every 48 hours it surfaces to transmit its information back to the lab via satellite.

The huge advantage of the gliders is that costs are drastically reduced as scientists and boats are no longer needed to be out on the ocean for days or weeks at a time to search for and monitor whales.

Using battery power, the gliders can travel for up to four months on their own before recovery.

Climate change? Maybe, maybe not.

Normally a large number of the whales are found off the south coast of Nova Scotia at this time of year, but lately they seem to be going elsewhere.

Davies says the tracking programme has found more of them in the Gulf of St Lawrence than their usual area in the Roseway Basin around southern Nova Scotia. Another researcher says many more than usual have also been spotted in the Bay of Fundy this year.

Davies says that while this may seem unusual, it is likely due to fluctuations in amounts and locations of the whale’s food source, tiny zooplankton. She also says that not enough is known of Right whale habits to say that changes in food supply or this ‘change’ in location are due to climate change. She notes there is a large natural variation, and studies have not been going on long enough to establish patterns.

By tracking where the whales are and when, she says the multi-year project is helping to add data to scientific knowledge of the whales, and that should also help in developing policies beneficial to the species survival.